Intro

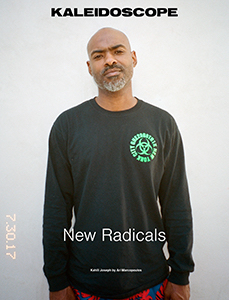

Interview with Jack Pierson, Kaleidoscope #31–Winter 2017/18–New Radicals.

Content

Gianni Jetzer: What are your most vivid memories of those “Hungry Years” you refer to in the title of your new book? How did you pick the title?

Jack Pierson: I had moved to New York in the early 80's finished school and gotten a job at a gallery. By Christmas time the gallery hadn't paid me for a couple of months and I was frazzled. A friend suggested we get what was known at the time as a 'drive-away car' people that needed their car someplace other than NY listed them with an agency so you could go in, chose a place you might want to go and they'd give you the car and even I think a stipend for gas. Then you'd have an agreed upon amount of time to get it there. There was one to Miami so, I managed to collect my pay in cash and we drove south right after Christmas. Once we arrived we didn't have money to get back so we took a 55 dollar a week room on the beach and got jobs. It was heaven. I know you're probably thinking '55 bucks a week, on the beach?!' But there were a couple of weeks that we returned to the room to find it padlocked because we were late with the rent. We is me and my friend Andre Laroche the fellow on the cover.

The Hungry Years is the title of a great Neil Sedaka song from the 70's when Elton John had rescued him from oblivion and he had a few hits again. It's one of my favorite songs and has become a standard. The basic theme is 'it was pretty great before we had it all'.

GJ: How do you usually begin to work on a book? What did you do in this particular case?

JP: When making a book it's usually because there's a group of work I have that I can sort of tell a story with. Some of these photos were in my first book called Angel Youth. In this case I was having a survey show at the Aspen Art Museum this year and seeing these photos on the wall again made me realize they had never really been presented in book form as photographs with a capital 'P' which to me means one per page with a lot of white space around them and the title. At the time I first began showing these photos they were kind of in opposition to photographs with a capital P. They were printed by a commercial outfit for families that wanted their snap shots 'poster size ' each one cost $9.99. I pinned them to the wall using bankers pins (I don't know why they're called that) they were something I used in another job I had in NY decorating windows for a surplus store. So, in other words I was being 'anti' as photos in the late eighties early nineties were very big and very handsomely framed so that they could compete with paintings. Not only did that not appeal to me I simply couldn't have afforded it.

GJ: In your “Self Portrait” you opted for a highly conceptual approach by retracing the life ages by fifteen photographs of beautiful young men. What about “The Hungry Years”? What is the concept? What delimits these works? How many images from the series did you exclude?

JP: I've never really consciously worked in series, that's another trope of Photography in the art world that I sought to eschew. The Self Portraits were made on editorial shoots for magazines and after a period where I sort of owned 'bad photography' out of focus, over or under exposed and un level horizon lines etc, I began to work for magazines and because I had access to better equipment and assistants I tried to do it better. At the end I had all these pictures that because they actually looked like magazine work, had an anonymous quality like these ones in The Hungry Years arrived having. Now they have a Jack Pierson quality or a 'snapshot' quality. At that time in 1990 those things were new it was kind of only me and Nan doing it and yes she did it first! So anyway I had all this work and I really liked it but it didn't look like art or Art. I created the idea of them being self portraits very simply, along the lines of 'every portrait is a self portrait '. It wasn't very thought out until after the fact.

The Hungry Years is not a series. It's just work I made at a particular time. Some of the images were taken in the early eighties some in 1989. They're dated 1990 because that's when I first printed them.

GJ: “Swiss Rebel” a new book published by Steidl includes for the first time the complete Panopticon of photographs that Karlheinz Weinberger took during his lifetime. From street photography in the 1950s to the portraits of rockabillies and bikers and pornographic portraits. Is there a chapter in Weinbergers work that you feel closer than others in relationship to your work?

JP: There's not really any aspect of Karlheinz’ work I'm not a fan of. He was as equally fluent in the studio as on the street and he had a keen eye for the sculptural qualities of his subjects. We share a love of the 50's, 60's, Elvis Presley and teased hair. Whether or not that connects our work, I'm not entirely sure.

GJ: It is interesting to see the notorious “outsider” Weinberger as part of Contemporary art today. Where do you position his work? Was he an artist or rather an ethnographer who used photography as documentation?

JP: I strongly believe being an ethnographer and an artist are not mutually exclusive although I'm pretty sure both Weinberger and another photographer not so dissimilar from him, Mike Disfarmer, might have considered themselves artists first.

GJ: You often use your friends as models. Weinberger did that too with the young rockers in Zurich as well as later with Hells Angels. He had his own flat and invited them over to hang out. What makes the difference between friends and strangers? Are there moments were things start to be confusing because you mix professional and personal relationships?

JP: I never really actively thought I was using my friends as models, I guess now I'd have to reappraise that, at the time though it wasn't conscious. Now I do more frequently photograph 'strangers', however I usually consider by the end of the process that if not exactly friends, they are not strangers. I don't really believe in the concept of strangers, not to sound 'airy fairy' it's just not how I feel. Whether they feel the same I'm not sure.

GJ: If you describe the mood in this portfolio is it rather Stairways to Heaven or Appetite for Destruction? Hope or despair?

JP: Well I'm only a cursory fan of Led Zep or Gun's and Roses so far my part of it at least I'd say it's more 'Blue' or 'Hejira'. Hope and despair are a given. Despair at this point in my life has become optional however. I'd cite Little Richard and Gene Vincent for Karlheinz Weinberger.

GJ: How would you describe the influence of Weinberger’s images on you? What is his contribution to Contemporary photography?

JP: I think the more people, or Contemporary Photography, as you say, learn that there are image makers outside of the chosen centers of culture the more humble and considerate we all become. That's a good influence, don't you think? More so than being a mood board for fashion, no?

GJ: Your work was created in the 1980s a decade where consumerism and creativity begun to form convergent lines. Do your works represent a subculture that resisted the commercialization of culture?

JP: I don't know that my work represented a subculture. I know I thought I was resisting the convergence of culture and consumption and still do to a large degree. I know this is perhaps debatable given that my artwork enjoys success in the marketplace and my photos are published. I just need to feel like a rebel on some level, even at my advanced age, otherwise why bother? I'm sure Jeff Koons does too and I wouldn't argue with him.